Some Words Get FIRs. Some Get Standing Ovations. Welcome to Article 194.

In India, speech is never just speech. It travels with context, power, platform — and often, protection. A joke delivered on a public stage can invite criminal proceedings. A social media post can snowball into police notices. But a remark spoken inside a legislative chamber, even when it stings, demeans, or shocks, often dissolves into constitutional immunity.

Share on social media

About Some Words Get FIRs. Some Get Standing Ovations. Welcome to Article 194.

This contrast is not accidental. It flows directly from Article 194 of the Constitution, which grants legislators freedom of speech within the House and immunity from legal proceedings for words spoken there. The provision was drafted with noble intent — to ensure that elected representatives could speak fearlessly without executive or judicial intimidation. But over time, that protective shield has raised an uncomfortable question: when does freedom meant to protect democracy begin to protect conduct that undermines it?

Why Article 194 Exists — And What It Was Never Meant To Do

Article 194 was never conceived as a personal privilege. From the very beginning, constitutional courts made it clear that the immunity belongs to the institution, not the individual. In M.S.M. Sharma v. Sri Krishna Sinha (1958), the Supreme Court emphasised that legislative privilege exists to preserve the independence and dignity of legislative functioning — not to create a parallel universe where constitutional values temporarily switch off.

The purpose was simple and sound: legislators should debate policies freely, criticise governments sharply, and express unpopular views without fear of reprisal. But that freedom was always tethered to function. The Constitution trusted that the dignity of the House would regulate the dignity of its speech.

What the framers never intended was for immunity to become an escape route for statements that have no legislative purpose at all.

When Location Began to Matter More Than Logic

The interpretation of Article 194 gradually shifted from why the speech was made to where it was made. This shift culminated in the controversial judgment of P.V. Narasimha Rao v. State (1998), where Members of Parliament accused of accepting bribes were shielded from prosecution because their votes were deemed protected legislative acts.

The Court reasoned that since voting was part of legislative functioning, anything connected to it — even criminal conduct — fell within privilege. While the judgment followed precedent, its implications were deeply unsettling. It suggested that once conduct is dressed in parliamentary procedure, the criminal law must step aside.

This was not constitutional confidence. It was constitutional discomfort, waiting to be addressed.

The Supreme Court’s Course Correction — Sita Soren v. Union of India

That discomfort finally found voice in Sita Soren v. Union of India (2024). In a decisive move, a seven-judge bench overruled Narasimha Rao, holding that bribery cannot be constitutionally immunised merely because it is linked to a legislative act. The Court drew a crucial distinction between legislative action and criminal inducement, stating that the latter has no legitimate nexus with parliamentary functioning.

The reasoning was careful, not confrontational. The Court did not weaken legislative privilege; it restored its purpose. Privilege, it held, is meant to protect the process of law-making — not to sanctify corruption.

“Privilege cannot be stretched until the rule of law snaps.”

Speech That Harms Without Legislating — A Harder Question

If bribery was an easier line to draw, speech posed a subtler challenge. What happens when a legislator uses the floor not to legislate, but to insult, demean, or trivialise serious social concerns? For years, courts hesitated, wary of being seen as referees of parliamentary debate.

But silence came at a cost. The idea that anything said inside the House is immune slowly detached privilege from responsibility. That is where the Karnataka High Court’s 2025 ruling becomes crucial.

Karnataka High Court: Nexus Is Not Optional

In 2025, the Karnataka High Court examined a case where a state legislator made crude, gendered remarks inside the Legislative Council. The argument of immunity was predictable. The Court’s response was not.

It held that speech which “outrages modesty” and bears no nexus to legislative duty cannot claim protection under Article 194. The Court stressed that constitutional privilege does not convert the House into a consequence-free zone. Speech must still relate to governance, policy, or legislative debate.

This judgment did not police content , it policed purpose.

Outside the House, Accountability Is Immediate

Contrast this with how speech is treated outside legislative chambers. Comedians, artists, writers, and citizens are routinely subjected to criminal processes based on perceived offensiveness or insensitivity. Courts examine intent, impact, and social harm with seriousness.

The disparity is striking. The greater the public authority of the speaker, the greater the protection — even when the speech contributes nothing to public discourse. This inversion of accountability was never envisaged by constitutional design.

Privilege Without Structure Becomes Entitlement

Experts and committees have repeatedly warned that uncodified privileges risk misuse. A 1997 report of the Department of Legal Affairs recommended clearer contours for legislative immunity, emphasising that privileges must operate in harmony with constitutional values, not against them.

Privilege that lacks boundaries becomes discretionary. Discretion, when unchecked, becomes entitlement.

What Reform Should Actually Look Like

Reform does not mean judicial overreach or parliamentary censorship. It means clarity. Privilege should protect genuine legislative debate, not personal commentary unrelated to governance. Internal disciplinary mechanisms must be strengthened, and courts should intervene only where speech clearly violates constitutional principles like dignity and equality.

This approach preserves legislative independence while reaffirming constitutional morality.

When Courts Speak in Harmony

Read together, Sita Soren and the Karnataka High Court ruling articulate a coherent constitutional philosophy. They remind us that privilege flows from purpose, and immunity follows function. The House is powerful but not powerless to values.

Article 194 was meant to serve democracy, not shelter its contradictions. When speech forgets this, courts do not undermine Parliament. They restore the balance the Constitution always intended.

Recent Posts

Can a Democracy Survive if It's Own Exec...

Read More

When Roads Become Traps and Rivers Turn...

Read More

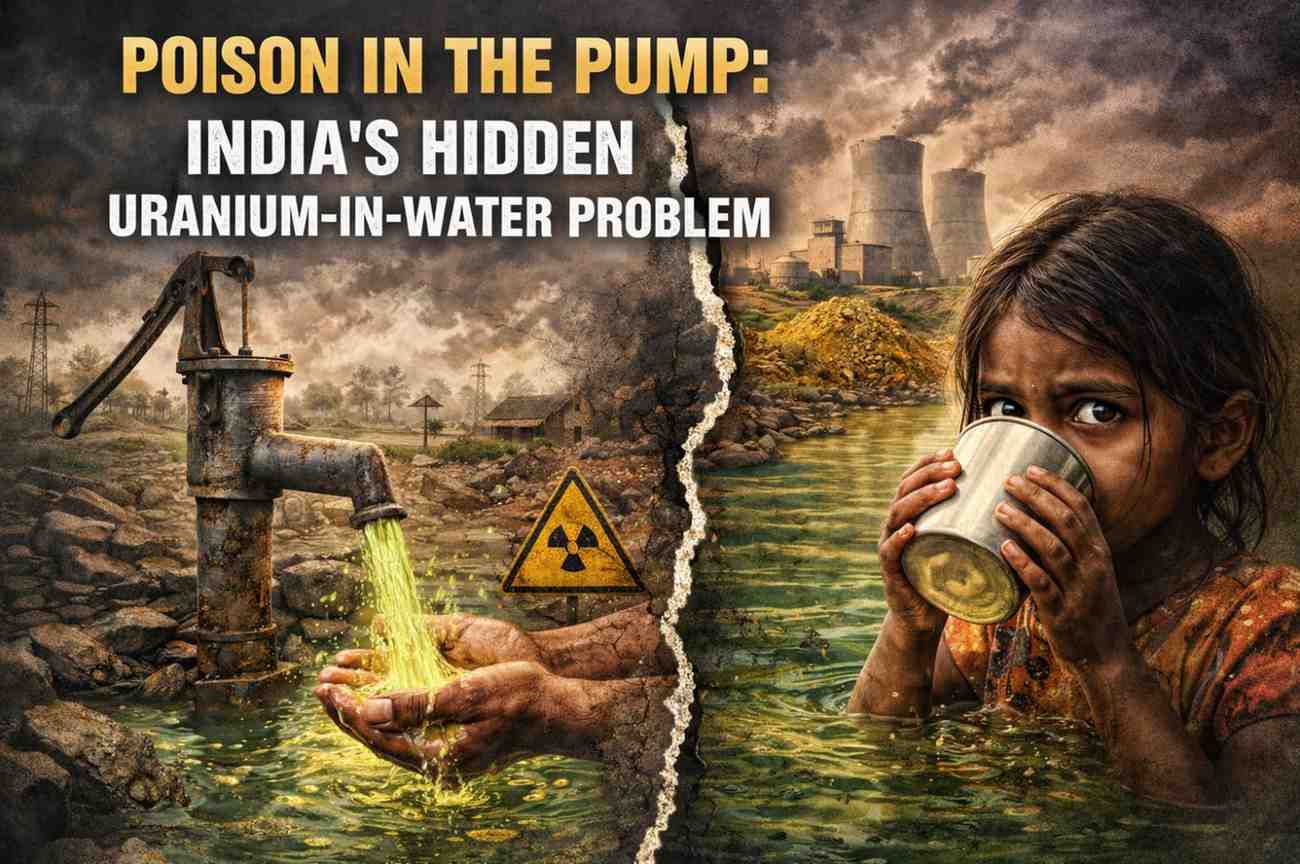

Poison in the Pump: India’s Hidden Urani...

Read More

Aravalli Hills: When a Hill Has to Measu...

Read More

Men’s Rights in India — Finally Getting...

Read More

Some Words Get FIRs. Some Get Standing O...

Read More

India Rewrites the Rules of Work: Why th...

Read More

When the Files Became Too Heavy: A Saket...

Read More