Can a Democracy Survive if It's Own Executive Defies the Judiciary?

A close look at the Karthigai Deepam controversy at Thiruparankundram hill and what it reveals about democratic health.

Share on social media

About Can a Democracy Survive if It's Own Executive Defies the Judiciary?

Democracy is not just elections and majorities — it is a structure of rules, institutions and mutual restraints. A core pillar of that structure is judicial enforceability: courts must be able to make binding orders, and the executive must implement them or, if it disagrees, use lawful channels (appeal, review) rather than simply refusing to comply. When an executive — through administrative officers or police — actively obstructs a High Court order, the event is not merely an episode of law-and-order friction. It becomes a test of whether constitutional checks and balances still operate.

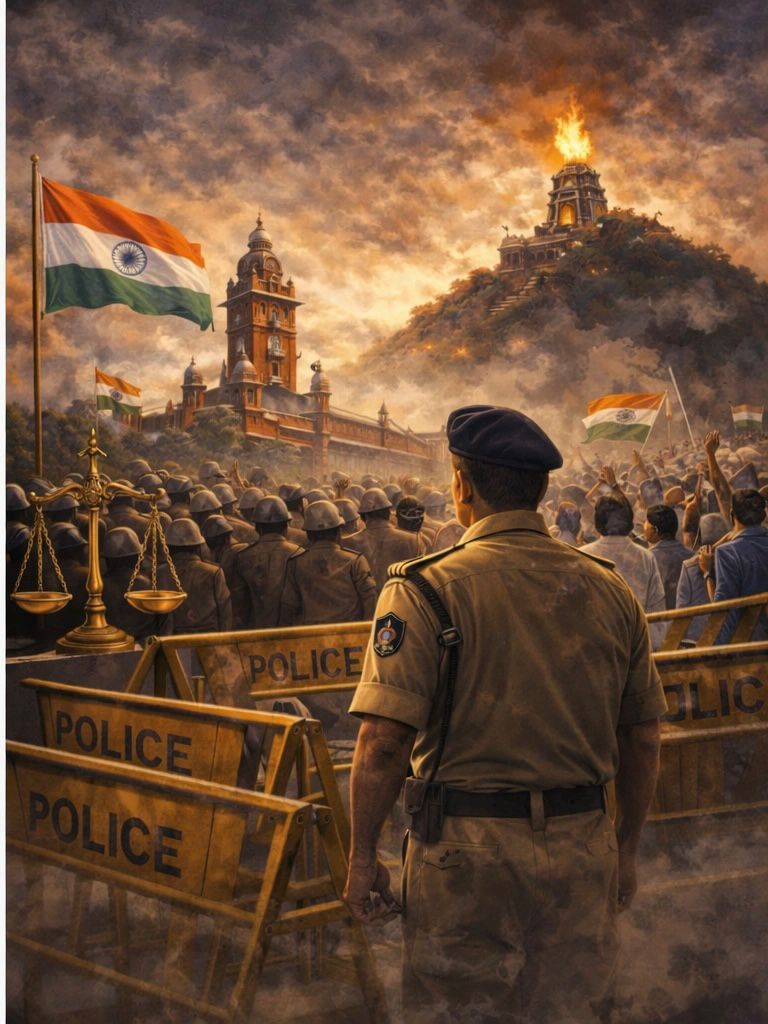

The recent Karthigai Deepam episode in Madurai (Thiruparankundram) — where the Madras High Court directed that the traditional lamp (Deepam) be lit at the ancient Deepathoon pillar and state authorities openly resisted and deployed large police contingents to prevent compliance — crystallises these concerns in stark terms. Below I set out a factual timeline based on reporting, explain why this matters constitutionally and politically, and consider the legal and institutional remedies available.

What happened — a concise factual timeline

- Madras High Court order permitting lighting at Deepathoon.

The Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court allowed writ petitions seeking permission to light the Karthigai Deepam at the ancient Deepathoon (lamp pillar) on Thiruparankundram hill, observing that the practice is a deep-rooted Tamil tradition and that the purpose of a Deepathoon is precisely to light such a lamp.

- State/administration resisted implementation.

Despite the court’s direction, district officials and the temple administration did not comply with the order as given; instead, officials cited law-and-order considerations and other administrative grounds, and the state subsequently approached higher forums. Reporting shows the state contested the practical effect of the HC order and moved in some instances to shift the lighting to a different spot.

- Large police deployment and obstruction at the site.

Multiple news reports and on-the-ground accounts documented significant police presence on the hill and in nearby approaches — including cordons, barricades and what local reporting described as a substantial deployment (media coverage refers to around 200 police personnel in and around the area) — effectively preventing groups from going to the Deepathoon to comply with the High Court’s directions. This heavy deployment and the manner in which officials enforced prohibitory orders led to confrontations.

- Clashes, detentions and political mobilisation.

The non-implementation triggered clashes, protests and detentions: some protesters allegedly tore down barricades; there were reports of stones being thrown and of the police arresting local BJP leaders and detaining protesters. Political parties and religious groups quickly made the issue a flashpoint, amplifying tensions.

- Contempt petitions and judicial response.

The matter moved back before the Madras High Court in the form of contempt petitions and urgent hearings. The court summoned senior state officials, including the Chief Secretary and the ADGP, to explain the non-compliance and directed them to appear (virtually or in person) as part of contempt proceedings. The State also filed special leave petitions in the Supreme Court challenging some High Court directions.

(Sources used for the timeline include The News Minute, Indian Express, Times of India, LawBeat, Mathrubhumi, The Free Press Journal and related regional reporting. See inline citations for each point.)

Why this is not just a local festival dispute — constitutional stakes

- Separation of powers and enforceability.

A court’s order is not a moral suggestion; it is a binding direction backed by constitutional authority. If the executive can routinely refuse to implement High Court orders (and instead use police to physically block implementation), the practical capacity of the judiciary to secure remedies disappears. Over time, this hollowing-out undermines the rule of law: courts may keep issuing orders, but they will become nominal if the executive can pick and choose which orders to obey.

- Police as neutral constitutional agents — not executors of political preference.

Police officers swear to uphold law and constitution; they are not instruments to deny court-ordered relief on behalf of political considerations. When law enforcement is used to prevent the execution of court directions, the institutional neutrality of the police is jeopardised — eroding public trust in state machinery. Reporting indicates that policing decisions in this matter were driven by state administration lines (e.g., citing prohibitory orders and appeals) rather than immediately complying until the legal process could play out.

- Contempt and the appearance of impunity.

The judiciary does have coercive tools (contempt jurisdiction, directions to officials, etc.). But coercive tools only preserve constitutional balance if they are used and enforced. The HC summoning the Chief Secretary and ADGP shows the court exercising its supervisory power; whether those summons and any consequent orders are complied with will be an important indicator of how seriously institutional boundaries are respected.

- Communal and political amplification.

Cultural-religious disputes can ignite communal tensions quickly. The Deepam issue has been seized by political parties and religious organisations; actions perceived as executive bias (either for or against a community practice) risk deepening polarisation and turning a legal order into a public-law crisis. Several regional reports highlight protests, counter-protests and appeals to law-and-order concerns.

Legal and institutional avenues available (what the courts and others can — and should — do)

- Contempt proceedings and binding directives.

The High Court can proceed with contempt actions against specific officers who wilfully disobey its orders, and it can issue clear, executable directions (for example, mandating police protection to allow the order to be implemented). The HC has already initiated steps in this direction by summoning senior officials.

- Interim supervisory orders — mandamus and protective relief.

Courts often issue mandamus to compel officials to act and can direct specific security arrangements (e.g., escort by central forces like CISF when local enforcement is seen as partisan or incapable). The High Court’s earlier directions included provisions for security; disputes over their implementation are precisely why supervisory enforcement mechanisms exist.

- Appeals and higher judicial review (Supreme Court).

If the State genuinely believes the HC erred, the regular channel is to seek review or special leave in the Supreme Court — which the State appears to have pursued. But filing a higher appeal does not justify immediate, unilateral non-compliance with a binding HC order while the appeal is pending; the correct approach is to seek a stay from the appellate forum.

- Administrative accountability and police neutrality reforms.

Executive agencies must adopt transparent operational protocols for implementing judicial orders — especially in sensitive communal contexts — and independent oversight (police complaints authorities, state human rights bodies) must be empowered to investigate any partisan actions. Media and civil society scrutiny will also shape incentives for compliance.

What this episode signals about democracy’s resilience

A single incident of disobedience does not necessarily mean a democracy has collapsed — democracies have internal disputes and crises frequently. What matters is how institutions respond:

- If courts can secure compliance — by exercising contempt jurisdiction, ordering neutral security arrangements and seeing them enforced — it shows resilience.

- If the executive repeatedly evades judicial orders without facing meaningful consequences, then the practical authority of the judiciary is at risk and the system moves closer to rule by power rather than rule by law.

In the Thiruparankundram case, the immediate litmus tests will be (a) whether the High Court’s contempt processes produce enforceable outcomes, (b) whether the State provides clear reasons and follows appellate processes instead of obstruction, and (c) whether law enforcement acts as a neutral implementer of court directives rather than a proxy for administrative preference.

Recent Posts

Can a Democracy Survive if It's Own Exec...

Read More

When Roads Become Traps and Rivers Turn...

Read More

Poison in the Pump: India’s Hidden Urani...

Read More

Aravalli Hills: When a Hill Has to Measu...

Read More

Men’s Rights in India — Finally Getting...

Read More

Some Words Get FIRs. Some Get Standing O...

Read More

India Rewrites the Rules of Work: Why th...

Read More

When the Files Became Too Heavy: A Saket...

Read More